Over three years ago, when I had just arrived in Brazil, I asked a family friend who’s a journalist why São Paulo’s conservative papers were in such an uproar over Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Lula wasn’t president. Did the right worry he might run again? “No one’s worried about Lula,” he told me. “He’d never run.”

Today many would call that answer blatantly wrong. And just as many see in the criminal case against Lula political machination. To be sure, Brazilians have had enough of corrupt politicians, yet Lula’s trial comes across to many as a smoke screen. He still represents the country’s social gains.

What cinema is fit for the current age of pessimism among the country’s middle and working classes?

This year, viewers need not look further than Affonso Uchoa and João Dumans’s Arábia. A story, first and foremost, about the possibilities of empathic imagination, the kind that American philosopher Martha Nussbaum extols in her books on literature and the arts; the kind that Lula’s breaching of vast class and economic divides once embodied, and which seems no longer possible. Latest numbers point to millions of Brazilians rolling back into poverty. The exorbitant gasoline taxes, cut after nationwide strikes, will come at a cost of cutting the already inadequate healthcare and education.

That’s just the preamble.

In Arábia, the preamble opens with a teenager, André (Murilo Caliari), biking uphill, listening to music. With the headphones on, he moves purposefully against the green hills of Minas Gerais, one of the country’s most prosperous states. Thus far we are close to the American trope of the open road. The country song, “Close Your Eyes I’ll Be Here in the Morning,” by Townes van Zandt, promises a story of ordinary folks holding out against all odds.

In a way, that’s exactly what Arábia is about. André lives in the proximity of a large factory. Day in and day out, he watches through his window the factory’s billowing smoke. It’s a wary site, particularly since André’s small brother has trouble breathing, and the thickness of factory plumes is directly correlated to his poor health. The two boys are home alone, living with their aunt, while their mother is away, for work.

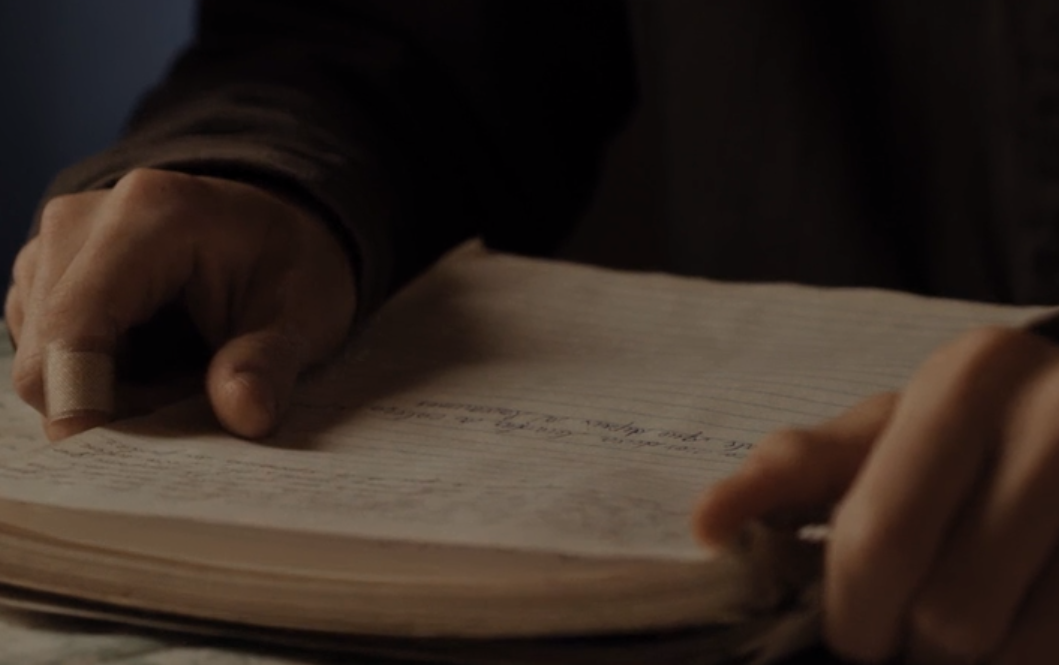

When a factory worker, Cristiano (Aristides de Sousa), suffers a grave accident, André is at the scene, looking down at the man’s ashen face, as the other lies, unconscious, on the stretcher. André’s aunt asks him to fetch clean clothes from Cristiano’s apartment. While there, André finds Cristiano’s diary—an unassuming notebook, with large, uneven letters. And while the handwriting doesn’t promise much, before we know it, we are plunged deep into a rich epistolary form.

When a factory worker, Cristiano (Aristides de Sousa), suffers a grave accident, André is at the scene, looking down at the man’s ashen face, as the other lies, unconscious, on the stretcher. André’s aunt asks him to fetch clean clothes from Cristiano’s apartment. While there, André finds Cristiano’s diary—an unassuming notebook, with large, uneven letters. And while the handwriting doesn’t promise much, before we know it, we are plunged deep into a rich epistolary form.

“I’m like everyone else,” Cristiano begins his recollections. “It’s just my life that was a little bit different. (…) In the end … all we have is a memory.” An unreliable narrator? Perhaps in a few telling silences, but overall Arábia’s tone is earnest. Cristiano documents the key moments in his life for the factory’s theater group he had signed up for. His artistic interest alone sets him apart. Yet as we’ll see, it is an attempt to find a firm footing in a world in which he feels alone.

In the voiceover, Cristiano guides us through a story that details the growing scarcity of manual work, the weakening of collective bargaining, and the impact these factors have had on the country’s working class.

If this sounds like a thesis, no worries, Arábia has memorable, even quirky characters (such as Cristiano’s friend, Luizinho, who bums off on the job and hates arugula), and a strong, at times almost monumentally epic composition. More importantly, it has a distinct pulse, a mix of quicker vernacular with loftier phrasing, punctuated by a varied musical score—an enjambment of rock and Brazil’s popular tunes, traversing registers, high and low.

The diary itself is a rewarding contrivance. What it lacks in immediate verisimilitude it makes up for in the richness, the gravity of the story, and the complexity of the characters. In this tale, there are no minor roles, really, and so it’s perhaps natural that, like André (nearest stand-in for the directors), Cristiano is also a conduit—he blends into the background, at times, as he inducts us into his world, and so becomes our eyes.

Cristiano’s story doesn’t pick up with childhood, as if, by contrast to André and his little brother, he didn’t see himself having one. Cristiano instead begins with a crime: he and his friend steal a car. But unlike the more scandalous Latin-American films, in which life of crime seems always one step away from the protagonists, Uchoa and Dumans elide a police scene. Likewise, the prison image is almost immediately subverted. We do see Cristiano in a jail uniform, but the friend he makes there, Cascão (Wederson Neguinho), is a loving, almost paternal figure. The first time we see Cascão he is feeding birds. If it weren’t for his deep skepticism about God—a recurring theme in the film—he’d be saintly.

After prison, on Cristiano’s first job, in the state of São Paulo, a co-worker tells him how an older worker, nowadays called “a troublemaker,” helped organize tangerine plantation workers back in the 1970s. He channeled their anger and resilience into successful negotiations for better wages. He might as well be speaking of Lula. “Today I don’t go hungry like my father did,” the worker tells Cristiano wistfully. But alas, that bargaining power, or solidarity and ethos, have eroded, and Cristiano himself first goes without pay for weeks, and when he complains, is let go, with bags of tangerines to sell on his own.

After prison, on Cristiano’s first job, in the state of São Paulo, a co-worker tells him how an older worker, nowadays called “a troublemaker,” helped organize tangerine plantation workers back in the 1970s. He channeled their anger and resilience into successful negotiations for better wages. He might as well be speaking of Lula. “Today I don’t go hungry like my father did,” the worker tells Cristiano wistfully. But alas, that bargaining power, or solidarity and ethos, have eroded, and Cristiano himself first goes without pay for weeks, and when he complains, is let go, with bags of tangerines to sell on his own.

Tellingly, there isn’t a job that Cristiano isn’t capable of doing. He is never seen slacking, but somehow sooner or later ends up being let go. And so must hit the road again. His journey, in the end, isn’t very far—São Paulo and Minas Gerais are neighboring states—but it will seem epic, by nature of repetition. Also by nature of Uchoa and Dumans’s consciously shaping Cristiano as Brazil’s Everyman in the transitive passages, in which he tells us he’s been around all kinds of people, the poor, the ill, “even the evangelicals,” and “everyone has a story. Even the quiet ones.” Thus Cristiano’s voice gives this random plurality cohesion, a powerful sense of communal destiny, where community is hard to preserve. Renato Teixeira’s folksy song, Raízes (Roots) on the soundtrack echoes van Zandt’s idea of permanence, but this time understood as rebirth, a “lesson that the universe teaches.”

Just when it seems that Cristiano is rescued from male-only company, the universe conspires against him again. He looses his lover, Ana (Renata Cabral), whom he met at a textile company. Like all his previous relationships, this one too falls victim to cruel circumstance, further stressing that workers in constant search of work never have a home. Though we could ask if Cristiano’s existential searching doesn’t come across a bit as a middle-class burden. And in the end, perhaps the film has done so well with critics and audiences alike, because, like Lula, it has found a language that speaks across the class divide. It filters working-class instability through a middle-class consciousness driven by a sense of justice. A justice—juridical, or perhaps only of fate—that the accident’s tragic outcome denies Cristiano.

In a sophisticated way, Arábia embodies a truism that the poorest are always screwed. It’s America, with no bailouts for workers who’ve lost their homes during the crisis, and with bailouts for bankers and the likes of Trump. It’s England in the buildup to Brexit, its Poland’s nationalist government rearing its ugly head, propped up by those who believe they’re getting a rough deal.

After a prosperous period, much of the world has (once again) woken up to what Brazilians seem to have always known—prosperity, even a modicum of it, is all too hardly won, all too easily lost.

In the end, however, we have much more than a memory. For Cristiano’s voice is a testimony, as much as it is—in the creative act of being shaped into a narrative—an articulation of a need for change.

Its silencing is its own demand.

Also see Affonso Uchoa on his film co-directed with João Dumans and their principal actor, Aristides de Sousa.

Arábia is currently playing at The Film Society of Lincoln Center.