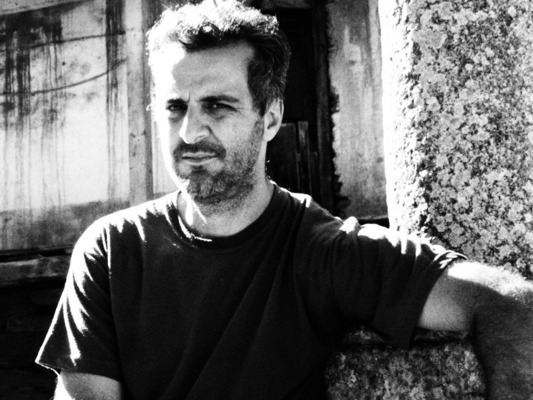

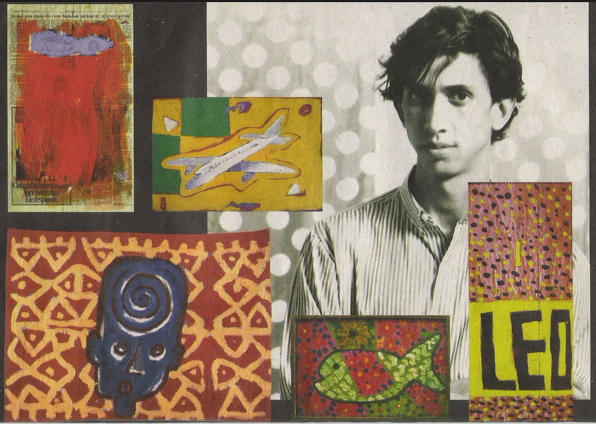

Passionate drawings of Brazilian artist José Leonilson, as well as his installation art, are the subject of Carlos Nader’s uniquely immersive hybrid documentary, JL’s Passion (2015), winner of the Best Documentary Prize at É Tudo Verdade / It’s All International Film Festival in Brazil.

Lyssaria spoke to Nader on Skype about Leonilson, Nader’s longtime friend and collaborator on art journal, Chaos. Leonilson remains relatively little known in the United States, in spite of his status as a major Latin American artist. He was recently the subject of a retrospective at Americas Society, and a subject of a comprehensive retrospective at Itaú Cultural in 2011.

How did you first come to José Leonilson’s tape recordings?

I became friends with Leo around 1987. In fact, he was my first artist friend. He was already pretty well known, though not as iconic as his art is in Brazil today. He had troubles with money, I remember, even till the end, but was supporting himself fully as an artist.

When we first met I was about 19. I just got back to Brazil, after traveling abroad for a year. On the suggestion of a friend I went to Leo’s house and proposed we start a cultural journal. We started Chaos, for which Leo made illustrations, at his home, and ran it till the Plan of Color (General Color was impeached in the 1990s).

The recordings themselves were Leo’s autobiographical project. He made them with others in mind, never just for himself. Since the start he intended that they should be heard. Those who knew Leo recognize this immediately when they play them.

I introduced Leo to Ricardo Ferreira Enrique, my best friend from adolescence, who also died of AIDS, in 2000. They became fast friends. Before Leo died, he made it clear that he was leaving the tapes for Ricardo to make something of them. Ricardo transcribed and edited them, and then wrote a first-person account, to be published. But at that point, in the late 1990s, the family blocked the book.

Why?

I wasn’t close to the story, because I was living in Rio. I heard that the family was very religious, particularly the mother, and didn’t want the book to come out. The family said, however, that this wasn’t it—they hadn’t known about the project, and were taken by surprise.

Years passed, but then Bank Itaú made a big exhibition of Leo’s work, called, Under the Weight of My Loves (Sob O Peso dos Amores), in 2011. When Itaú called to ask me if I knew the artist José Leonilson, I said, “My god, of course!” I made an exchange with the bank – I’d make a traditional institutional documentary for them, with interviews, etc., and Itaú and Leo’s family would let me do something with the tapes, since I’ve known the recordings ever since Leo made them.

You gained the family’s trust?

They knew me as Leo’s friend. And also, many years had passed – it was a different moment, they were more open to the project. Leo’s sister is in charge of his archives, and she gave me permission.

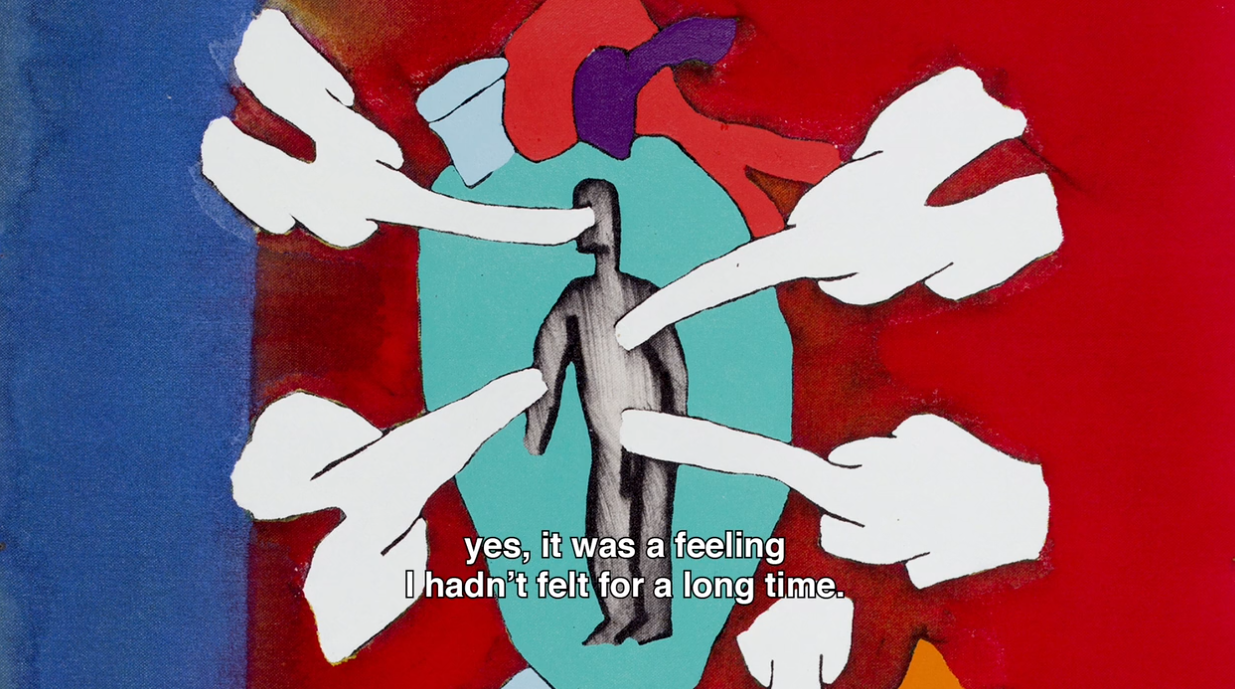

Drawing by Brazilian artist José Leonilson, as shown in Carlos Nader’s documentary, JL’s Passion (2015)

What touched you in Leonilson’s work?

I’ve always had a tremendous empathy with Leo. I remember arriving at his home one day – he was working in his garage on a piece that’s now worth over a million reais and is very famous, There Are So Many Truths (São tantas as verdades), in which he notes the names of everything he likes, rock groups, artists, etc. And when I walked in, he looked at me and wrote in, “CHAOS,” the journal’s name, even though the word almost didn’t fit anymore on the painting. Despite Leo being older than me by about seven years, we talked a lot – about homosexuality, love, anything. We joked it was because we’re the same sign, Pisces. We let our emotions show, shared a sense of solitude, idealization of love. Romanticism, you could say.

That romanticism is very present on the tapes.

It’s also funny, because Leo wasn’t like that. The tapes – romantic, ingénue, sentimental – reveal his artistic persona. Leo in real life was feline, playful, sarcastic. He made jokes all the time.

Are the tapes then a literary alter ego, a projection?

They’re Leo, but somehow filtered. I don’t want to use the word, “essence.” It’s hard to say.

What touched me in his work – and what Leo taught me when I met him, and after his death as I was making the film – was that it’s possible to extract from one’s work certain simplicity. Simplicity can contain complexity, in fact. It does not need to be a simplification.

Leo’s work is not purely conceptual, even though most of Brazilian art in the 1980s was. In his case, there’s abstract figuration. The figurative – a person – is in a sense Everyman. Leo was never painting just one person. Even if he had someone specific in mind, he combined persons, and figuration with symbolism. That’s what’s in those tapes, in a sense. When I first got them, I thought, “My god, who’s this person?” I had read the transcription of about twenty hours of tapes that Ricardo had made. Today it would have been more, because back then, in a pre-digital age, Leo would erase and re-tape sections, etc. But who was this guy? I couldn’t recognize him. Yet this persona –universalized, filtered – is somehow very close to his work.

The tapes inform how we see the works and vice versa, and there’s humor and sarcasm, for example, in the parts with Hollywood movies.

I stressed those parts, partly because to make a film I needed images. But in my other documentary, Leo does speak about how the artists of his generation embraced Pop Art and popular culture. Brazil was under a dictatorship, and the artists were the heirs of conceptual art, but also broke with it, and embraced Pop. Our journal, Chaos, did that.

The film speaks of death but it’s also a story of life.

Yes, in a way, the Christian concept – and I don’t mean it in a strictly religious sense – of resurrection, conquering death, is always present in my films. In Common Man (Homem Comum), for example, in both my narrative and in the parts based on Carl Dryer. In Leo’s case, he gained immortality through his work. He died, but then we see his last installation, made inside a chapel, with strong erotic elements.

When he speaks on the tapes about wanting to swim “like a fish in the vast of ocean” of flesh, it’s a very erotic moment. Desire is in fact what makes his work so vibrant.

Yes, back then it was a time of sexual liberation. We lived under the dictatorship, and some people disappeared, and died – plus there was persecution of gays, as there is still today – but there was also a sudden breath of freedom. Leonilson loved going to gay clubs. He felt very lonely, but he did have a regular sex life. I guess he felt alone in the sense of not finding true love. When he did find it, he discovered that he had AIDS. He was therefore haunted by solitude, by not having lived the life in which he could fully share the love of another man.

In this sense, you can really feel the weight of his family’s religiousness, even though they love and support him.

The family had a huge love for Leo, and vice versa. But then the Itaú show is called Under the Weight of My Loves – love is a weight. I recall the music I used in the film by Joy Division, “Love Will Tear Us Part,” which was a bit like a hymn for us at the time. I identified with it. The lack of a person to love was a theme we shared.

I was curious how hard it was to get clips, like Madonna’s.

I knew that Giovanni Bianco, the graphic artist who had done covers for Madonna, lived in New York and was friends with her. When we first spoke with the label, they said Madonna had no interest in her music being in the film, so we said we’d reach out to her ourselves. The label people kind of laughed at us. But we did. Madonna was friends with Keith Herring who died of AIDS, and also with Basquiat (Leo loved Basquiat), so when she found out about Leo, she helped us. Her lawyer called us directly, and even helped us with the rights to Cole Porter’s song that Annie Lennox sings in Derek Jarman’s film, Edward II (1991), “Every time I say goodbye.”

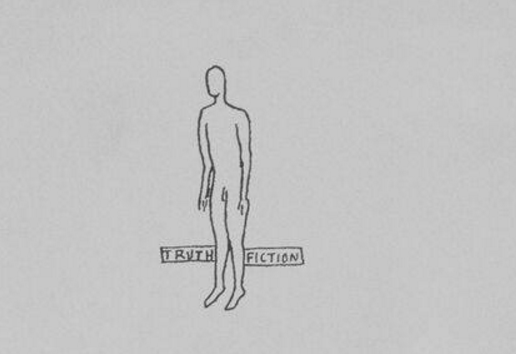

Truth/Fiction, one of José Leonilson’s famous artworks, as shown in Carlos Nader’s JL’s Passion

How did you then arrive at the final structure, mixing tapes, music, films and Leonilson’s art?

I needed first to understand what Leo wanted, since he himself wasn’t sure. It’s important to remember that in the 1970s there already existed a tradition of artists making tapes. Andy Warhol had made many recordings, and then published a diary, which was almost an equivalent of society pages, in his wonderful book, POPism (1980). [Brazilian artist] Hélio Oiticica also made tapes, which he later called Hélio-tapes, at a time when he was living in New York. These were the two artists Leo adored. Oiticica was a huge reference for Leo.

In the end, I found a form that’s fictionalized. I’m thinking of “fiction” as a word that means, “give form,” from Latin, and was used in “give form to clay,” in the myth of creation. I made a film in three acts, joining certain characters into one, as Leo used to do in his tapes and work. A bit of Truth/Fiction, as one of Leo’s works is titled. Pure Leonilson, and something I do as well in my work. It took me about three years between the screenplay and this final concept.

In my film, there are different variants of what Leo says and how this relates to what’s on the screen. There’s a literal relation, when Leo says, for example, “I’m feeling empty,” and his artwork, with the word, “Empty” appears. Some direct associations are Leo’s, others are mine. Then there are the poetic ones. It was only when I found those varying layers and links that the film started to take shape.

In a way, that’s where the art really lies – in creating a dialogue that goes beyond the literal.

Proust and Brazilian artist Tunga have said that doing art is bringing into a relation two things that it’s hard to explain why they go together. For example, when you speak of the HIV virus, and there’s the image of a red canvas, what’s the link? Art is the mystery inherent in an association of disparate elements – or epiphany, as Proust and Tunga used to say. Via epiphany, something new, often indefinable, is revealed.

JL’s Passion will play in the LGBTQ Brazil film program at the Museum of Moving Image (MoMI), on July 29, 3:30pm, co-presented by Cinema Tropical and curated by Ela Bittencourt. Full program on Lyssaria.