Ismael Caneppele’s Music For When the Lights Go Out plays in the LGBTQ Brazil film program at the Museum of the Moving Image, on Saturday, July 28, at 2pm, co-presented by Cinema Tropical. Winner of Art Doc award at Sheffield Doc Fest, it will play next at DokuFest.

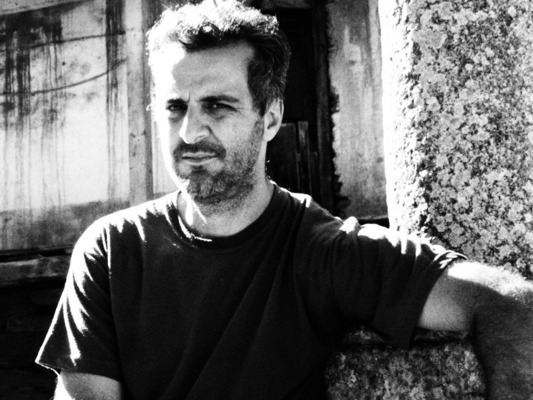

We interviewed Ismael Caneppele via Skype about his approach to this unique documentary hybrid film.

How did you arrive at the protagonists in your film?

I lived in the small town in the state of Rio Grande do Sul where the film takes place. I left it when I was 17, because I wanted to work with art, particularly theater. I was interested in the work with Gerald Thomas and so I moved to São Paulo. But then around 2006, I felt like I had lost my adolescence somehow, because every time I returned I heard stories from friends about the life that I was no longer participating in

I then met a girl younger than me, who told me stories about her life in the town. She kept a diary, but her mother burned it upon discovering it, and only a few pages survived. She gave me the surviving pages, about 10, of narrative and sketches of protagonists. I loved the way it was written, so I fictionalized the things that happened in those pages, and in the place, and wrote a book – a “documentary-fiction.” The only thing that I changed was that I created situations to tell a bit more. But I kept the gender of all protagonists except the main one. I wrote her as a man, and so in essence it was a gay romance between two young men.

The book was published by Jabuti, in 2007, but unfortunately the publisher ended up closing down, so now it’s impossible to find.

At that point I was already writing another book, and ended up making a screenplay based on it (The Famous and the Dead, 2009), working as an actor on that film, etc. Since I never studied cinema, this was my first time participating in the film world. The film did very well; it won a prize at the Festival in Rio de Janeiro, and then went to Locarno, etc. After that, I started to be asked to write a screenplay for Music When the Lights Go Out, but I didn’t want to repeat myself. I wanted instead to find a way to bring a documentary aspect to the film. And so my plan was to return ten years later to the town where I lived, and where the original girl wrote her diary, and observe with my camera who are the people in the same places she I knew, and see if I can find any similarities with the people I described, get closer to them and eventually hand them the cameras, so that they could film themselves, as if writing their documentaries with the cameras. That’s what I had in mind.

I got interested in Emilyn (Emilyn Fischer) – looking for protagonists long-distance – actually thinking that she was a boy. I had in mind to do a gay story, what it’s like to be a boy, and to be gay, in that small conservative town. It was only when I actually got to meet Emilyn that I realized she was a girl. So it was as if I were returning to the girl who wrote the diary originally. Except now she’s a girl who wishes to be a boy.

I must say that Emilyn changed all of my preconceived ideas. I discovered that I had a very cis vision of desire, and that the trans experience was very different. I discovered that the body has many more vectors, and that simply thinking along the lines of passion for a girl or a boy just isn’t enough to encompass it. We tried to tell the story of the body, a story that starts with the body. And the body doesn’t see its object of desire

There was the process that Emily needed to go through with this idealized masculine body—this was the process that Emilyn went through with Julia (Júlia Lemmertz). This way, an internal narrative that emerges. In the end, Julia also takes off her shirt, which is part of Emily’s struggle—I think that scene is in a way a re-encounter with the body.

Speaking of cis visions, I realized that when I began to speak about the film, I had a tendency to speak of it as a “lesbian” romance.

If you see Emilyn as a girl, I guess, yes, it is a lesbian love.

But in the film Emilyn constructs, and is, a character – which is Emilyn being Bernardo.

Yes, I hope that people discover just how driven we tend to be by gender. It is as you describe, but is also much more than that

It made me think of the outside pressure that exists outside fiction. How we are always being codified.

For example, when I met Emilyn she working as a shoemaker, in a shoe factory, with 500 other shoemakers, doing very physical work. She has also worked as a security guard. She lives in the poorest part of town, and I needed to take great care to make sure that she could feel herself an author of this work. I told her she could be Emilyn the actress, or Emilyn the actress who was Bernardo as a character, or she could create another fake name for the actress who was being Bernardo, and so on, and so on. I gave her all the options.

A way to give her complete freedom that she might not have in real life?

But in a way, in the end, she really does have that freedom. I assumed that Emilyn would be full of internal antagonisms or contradictions – wit her family, her name, her relationships, But in truth, Emilyn is loved and accepted by family, she is adored in the school, she has relationships with girls who love her. She has an identity that is very well resolved. The only thing that we discovered were the issues she had with her body – not liking to take a shower without clothes, not liking having breasts. So we just worked on that part in the film, in the part of the friendship, and the “apprenticeship” she has with Júlia as an actress, in which she gains trust, gains confidence, acceptance.

But then there’s the question of rejection –

Yes, and it’s really more than that. Because Emily has to deal with this idealized masculine body she’s constructing that’s in a way a dead end. She needs to exist in the town with it, which denies her her own physical, natural body. This was quite complex in the film, how to best work on this. So it wouldn’t be invasive.

That moment on the motorcycle, when she has an interaction with a naked male body, that embrace is the first ever for her. And that whole idea—that for her to achieve the object of her desire she must somehow “kill” her body—it’s a concept, but for Emily in a sense it’s an eternal question. An eternal struggle with and inside the body. There is no place to create a definite narrative of complete redemption, closure.

Is the young man who ends up nude with Emilyn in that scene an actor?

No, he’s not. He’s an architecture student from the region, and in fact it was quite delicate to work with him. He signed up to be in the film, and had a very powerful connection with Emilyn but in fact knew her for the longest time as only Bernardo – because Emilyn when she was on the set was always Bernardo, and so everyone was relating to her as a man. It was on slowly that everyone on the set started to realize that Bernardo was in fact Emilyn. And you could say that the boy had a homophobic approach at first, it took time to deconstruct that initial reaction.

That feeling of complete comfort and yet a great risk is a constant tension in the film.

Nobody on the set had known Emilyn before, but the film took thirteen months, so in a way they found in each other a community, discovered similar interests, and are close to this day.

So you had thirteen months and 300 hours of footage.

Yes, in the end we needed to have two stretches of editing. Essentially everything I did in the town was being filmed. I would just jump into a car with the group and film, and then we would make pre-cuts and watch them with the group. Sometimes there was no one but myself to film; sometimes we had a small crew. But in truth, I could only make this film because I had never made anything before, and because my producers were always very supportive. It’s the kind of film you can only make when you are new to cinema, and young.

When did Julia join in? She comes much more from the film world, film industry.

I started with the documentation, the experimentations with Emilyn, but I felt very much a stranger who entered into their house, even though Emilyn and her family treated me so well. I had met Julia when she was on the jury at the Festival in Rio de Janeiro, where she watched the film, and she was always very open to working with me. We would exchange ideas, I’d watch her do theater, etc. And so in the process of becoming close to Emilyn and her family, I begin to think of Julia as entering into it as a semi-fictional character, a stand-in mother.

Julia is a very popular face on Brazilian television, etc., and so I felt I wanted her to be part of the film, because there’s this fascination with her presence, and yet she breaks out of it, that aura, very easily, due to her theater background. She has really done all kinds of work. And she was very much into the project. She just wanted to change a bit of the visual—but didn’t want me to tell her anything ahead of time. “I’ll come and do anything you need,” she said. She came for the very last week of the shooting, about ten days. She came alone, and drove from the airport to Emilyn’s house. She spent time with Emilyn’s mom in the hospital, and then lived and cooked in the house, spending time with the family—all this was being documented. Julia had had a real closeness with [the great documentary filmmaker] Eduardo Coutinho; she had interviewed him a few times, and so she had a feel for the documentary form, and the documentary spirit. She became crucial to the entire process, to the point that when we were editing, we had 230 hours of raw documentary footage and about 70 hours with Julia. And in post-production I asked Julia to do voiceover for some moments that I had filmed with Emilyn, in which you could hear more voice—so in those moments Julia and I essentially merged into one person.