Maddening, exasperating, overindulgent. Without a doubt, Mexican filmmaker Carlos Reygadas can be all these things. And yet, his latest film, Our Time (Nuestro Tiempo, 2018), in which a married couple nearing middle age must come to terms with love and desire, can also be intensely moving, if profoundly sad, and unnerving. For sure, Reygadas sticks a bit too conveniently to the point of view of his male protagonist, Juan, whom he plays himself. And indeed, it is more than a bit creepy and voyeuristic to see his real-life wife, Natalia López, play his onscreen partner, Esther. Is it because “art imitates life” is an outworn cliché? More prosaically, at two hours and fifty-three minutes, Our Time feels somewhat bloated, as the plot peters out, and the sense that the characters may come to any real terms dissipates, leaving us in doubt just how far the metaphors, or the imitation of life, are being taken.

But then diffusiveness isn’t anything new in cinema, or art. There are the incessantly bruising goings-on of Bergman’s couples, in Scenes From a Marriage (1973), or Saraband (2003), to name but two films. There is the weary, exhausting night of Cassavetes’s Faces (1968). Beyond cinema, we could add Strindberg, Ibsen, Dostoevsky—all the torturous affairs between men and women destined to love and hate, a bit of both, in fact. Reygadas belongs to the long lineage of what, for lack of a better definition, we might call hysterical men (there have been hysterical women, so why not, even if the term is by now outmoded?). Panicked about aging, sex, desire, physical infirmities, full of insecurities, a raging need to control, an unhealthy dose of self-loathing, spite. Readers of French writer, Michael Houellebecq, will also recognize these traits in his women, though there is never any doubt that the author is in fact speaking through them about himself. Channeling his inner Madame Bovary. And Reygadas does very much the same, though goes a step further by casting himself as a conflicted, pained, belittled, resentful, but also domineering husband. Such ventriloquism does not make for pretty viewing, and yet, for those who have stamina and patience, it can be rewarding.

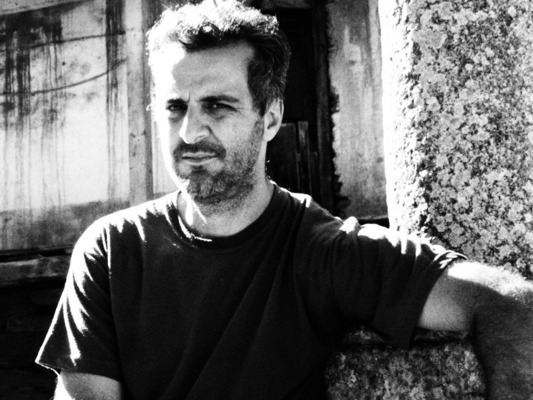

Natalia López as Esther in Carlos Reygadas’s Our Time

For one, there is Reygadas’s genuine feel for nature. Its beauty, majesty, savagery. In the film, Esther and Juan are dedicated rancheros. There is some hidden resentment in this arrangement. When Esther goes to the city one night, to the Philharmonic, we get a sense of her previous life, in which she was a well-regarded musician. Why did she give it up? For what? We get no sense of her background, only that her relationship to Juan is filled with tenderness, and care. The two appear to tiptoe around each other. But then there is also a sense that the expansiveness of the plains that surround them, the simplicity and fullness of this rural life, are not lost on them. Presumably, this is because Juan is a poet, and the countryside, with its roughness, provides raw material for his work—a rather blasé treatment of poetry, which does little service to actual practice of writing. But never mind. The family life is clearly replete with love, and the most devastating part—quite earnest, on Reygadas’s part—is that somehow that love, that care, is not always enough. The children are growing up quickly; they are fleeing the nest. Esther is beautiful, and much adored, but the sexual attraction between her and Juan simply is not there (at least not on her part). When she starts romancing Juan’s friend, Phil (Phil Burgers), a bearded, burly horse-breaker, her genuine affection for another, which goes far beyond mere sex but also remains ambiguous, tests how far she and Juan can go in their arrangement: They had agreed to be free, to sleep with others, as long as they talk about it. But now somehow this agreement does not hold. Juan is cruel, manipulative, oppressively talkative; Esther is sullen, wounded, increasingly crushed by Juan’s obtuseness and interventions. Even worse, Juan goes as far as to communicate with Phil, via email, behind Esther’s back. Suggesting he was wrong, but will go along with the affair, as long … What, exactly? All to keep her, but also to re-insert and reaffirm himself, while also wanting to keep her satisfied. Happy? We can’t be sure what happiness might mean in this scenario, yet Reygadas’s willingness to explore the lengths to which Juan goes in spying on Esther, in his jealousy over her beauty, his sheer toxic nervousness over losing her, all this is a lot more bracing and honest than what the majority of dramas have delivered this year.

Which is not to say that the machismo of Our Time is not troubling, or that the constant parallelism between nature and men, albeit true, does not feel strained. There is the genuinely terrifying, agonistic scene when a raging bull attacks a horse—shots of hot, drenched, entrails oozing out of the murdered animal, as the bull, its black body bloodied, paces manically, a farmer hidden inside his cart, lest he too be slaughtered. Something doomed and ominous in our DNA, if we consider ourselves close to this murderous beast that simply does what it must, whenever provoked. But then again, Reygadas always seems to think of himself as a faun, half-man-half-beast, deep inside grotesque, no matter how momentarily inflated. In this sense, he does not hide his naked fear of being ribald, blind, frightened. Perhaps there is more reassurance in knowing one’s smallness and pettiness, no matter how scary the half-truths, or how fleeting the premonition of them, than in pretending otherwise? The golden light of the prairie seems but frail consolation for what this animal loses as its prowess ebbs. And ebb it must.

Tenebras lux.

Carlos Reygadas’s film played recently at Viennale, which took place in Vienna, from October 25 to November 8