My stay in Tiradentes, Minas, where the 22nd edition of Mostra de Cinema de Tiradentes, is still taking place, was brief. And yet, it was enough to sense the intensity, both of the films and the debates, which I associate with it, and which tend to reverberate, like a crushing wave, throughout the year, at other national festivals.

The theme of this year’s Tiradentes Festival is “corpos adiantes,” “bodies forward,” a theme that Cleber Eduardo, who oversees the festival’s curatorial team, summed up as cinema’s capacity to create “bodies for the future, and the future for those bodies.”

The body’s force was felt in all the films I saw. A rush to portray, to acknowledge, depict, verbalize, give form. To bodies trans, bi, lesbian, gay. Bodies for which there continues to be a confusion in the Portuguese language, such as when I began looking up the particles for “a transvestite,” which in Portuguese publications has appeared as “a transvestita” (female particle), or “o transvestita” (male particle). During the debates, however, there was a clear call for self-definition, which I imagine could help avoid grammatical equivocation (in this case, employing only “a transvestita.”)

For the first time, Mostra now has an application process that asks directors to declare their race and gender. I think some basic facts need to be quoted here, pointedly recalled by one of the festival’s new curators, Tatiana Carvalho Costa: Among over eight hundred shorts submitted this year, one hundred and eighty were by black filmmakers, and among those 60 by black women. “A significant number,” said Carvalho Costa, “though it certainly does not come close to what we would like to see, considering that half of Brazil’s population is black.” She also reminded the public that most of the women presenting shorts at the festival will most likely never get to make a future film (something that is, alas, a very global trend for women filmmakers).

As Eduardo noted, about 25% of filmmakers submitting refused to declare their gender and/or race, leaving the rubrics blank—all bearing male names, some offering antsy responses, such as, “human being.” But among the audience, there was little patience for such outright dismissal of how gender and race continue to play a role in cultural power dynamics. Followed by a call from trans women to stop casting cis actors in their roles, given that trans actors are readily available.

Cris Lyra, director of Quebramar

Above all, the body wants to be acknowledged. In the shorts program for “Bodies Forward,” in the film, Quebramar, by Cris Lyra, the young lesbian women speak of fear—of never being seen as “complete.” Auto-completion still remains out of reach for many. In the film, an innocuous New Year’s Eve display of fireworks reverberates as trauma, of gas used by military police against the young students who had been part of the Occupy movement in Brazilian high schools.

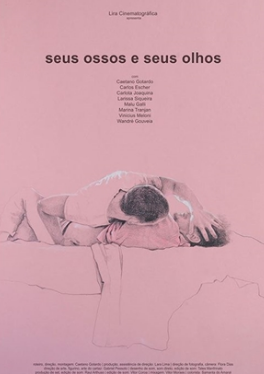

Poster for Caetano Gotardo’s Your Bones and Your Eyes

Bodies verbalize. Sometimes endlessly, obsessively, as if there can never be enough language to cover up the agony of rejection, of someone else’s brusque, ruthless denial of one’s own body, and personhood. The Proustian bitterness, when a madeleine offered is laced with venom. In Caetano Gotardo’s feature film, Your Bones and Your Eyes, which opened the official competition, the body needs not just to be seen, or held, in order to withstand the tide of overwhelming memory, a memory which returns as panic—or in Gotardo’s film, in which he also acts as the main protagonist, as a series of seemingly orderly tics, which, nevertheless, betray inner turmoil—it also needs to be grappled (literally, as Gotardo stages sex scenes as a series of tackles). It seeks comfort to the point of despair.

A rush to nakedness, exposure, the need to glorify every inch of flesh and flush of desire, powers Superpina, a feature by Jean Santons. A carnivalesque orgy, before the tide of censorship sweeps it away.

Tiradentes Festival Audience watches Superpina

But bodies also organize. In their documentary short, Tell It To Those Who Say We Have Been Defeated, by Ariano Bermfica, Camila Bastos, Cristiano Araújo and Pedro Maia de Brito, the directors capture the occupy movement of “sem terra,” “without land.” By night, groups carry torchlights, basic articles of clothing, water, food, and plant the first signs of their presence. A silent, clandestine movement forward, “bodies adiante,” that communicates a powerful sense of purpose and, above all, of community. A keen understanding among Brazil’s young generation of filmmakers of history as stories from below.

Peripheral bodies move center, to claim their place, exert gravitational force. Such is the case of André Novais de Oliveira’s hailed Long Way Home, with one of Brazil’s most talented performers and dramaturgs, Grace Passô. And while Long Way Home’s focus on the filigree fabric of the everyday gives no inkling of Passô’s natural fierceness (which, I will admit, led me not to love the film as much as most of my colleagues did), the film’s limpid beauty, the expansiveness of its humor, is the embodiment of how Brazilian cinema’s realist bend imbues its fiction with gravitas.

Bodies bear historical, physical markers. After the debate of Felipe Bragança and Catarina Wallenstein’s Bring Me the Head of Carmen M. turns tense, we seem to “lose our north.” We are debating Carmen’s “cannibalizing” of Brazilian samba—singing samba at a time when, as one black gay musician (played in the film by carioca musician Carlos Sacramento) points out, “to be gay was a crime, to carry a guitar with you was a crime, to sing samba was a crime.” So many transgressions against the body, one begins to lose count.

We don’t get anywhere with Carmen. Played by Wallenstein, she represents so many things—herself, Latinas, Brazil—she practically implodes. How poignantly strange that the woman who was sent to act as the Ambassador of good will between Brazil and the United States is being resurrected to serve yet another grand idea. Yet there is a gestural beauty in the film, an eloquence in the slippage between actress and role, between temporal frames, in the deliberate blurring of lines that seems to want to remind us that History is flesh.

Still from Bring Me the Head of Carmen M.

Still, we don’t get anywhere with Carmen. When I take the plane back, I recall what was said at the debate: Carmen Miranda sang the samba in the context of the 1930s. It is the context of Semana Moderna, the Week of Modernist Art, of Oswaldo de Andrade and his anthropophagic manifesto (in my mind, I add: when cultural cannibalism becomes hip, enters public parlance. Brazilian artists will do well by it).

So there is Carmen’s body in the big turban, bananas in her crown, the mirror she will die with, the woman’s vanity, strength, folly. There is Carmen in her myriad addictions, the melancholy, tragic Carmen.

Yet, as I think of her, it’s clear that Carmen had a calling card. In the end, perhaps the only card she had left—

She was white.

At that time, there was talk about “embranquecimento,” “whitening” the Brazilian race, a preoccupation of the ruling classes since the time when slavery was abolished in Brazil, in 1888.

The mixed message of Carmen’s canonization, as it played out in popular culture, was that Afro roots and black Brazilian culture could be mainstream … if the performer was white.

That is why Carmen can’t be a figure, or a body, for the future. It is difficult to present her as such without coming across as anachronistic. Regardless of her personal love for samba, her adamant insistence on bringing black and mulatto musicians with her—she fought Hollywood studios over this and sometimes won, while she championed other carioca musicians, as Bragança poignantly recalled during the debate—regardless of the fact that she was a driven artist who did not hesitate to transgress, Miranda, as immortalized and naturalized by popular culture is, from the start, a mix of high-flown but also toxic ideas.

On my way to São Paulo, I recall some of the facts from my recent readings on the 1930s (admittedly, still perfunctory): Getulio Vargas abolished the Black Party, a Frente Negra, in 1937. In a racial democracy like Brazil, there could be no place for a party that wished to fight for black citizens’ rights. Research and public discourse about racial inequality were suppressed. This too were the 1930s.

How to place Carmen in this context of prolonged silencing, if not as a beautiful yet profoundly troubling “assombração,” a phantom that haunts us with the persistent rattle of her bangles, whose faked high pitched voice nags at us? A reminder of an unjust social pact.