In one of my previous lives, I was a director of an arts foundation in New York, and during over a decade I was often reminded what incredible resourcefulness, resilience and sheer force of creativity teenagers possess. Amidst the foundation’s grantees (grants were to attend college), I often find myself thinking of the girls I came to know who, before they even worried about the exorbitant costs of college education – not just private but for some also in public schools, depending on whether they were eligible for aid – had to fight their own families for the right to education. Girls who fought not to be married off, not to be abused, verbally or physically, who sometimes had to leave home, and strike it out almost entirely on their own, before they even set foot in a classroom. To watch them not just succeed but excel felt like a miracle. But then “miracle” is a fraught word. It removes the sense of agency, when I know that it was the girls’ sheer grit, focus, determination and creativity that allowed them to imagine a better place for themselves, and having imagined it, to then slowly reach it.

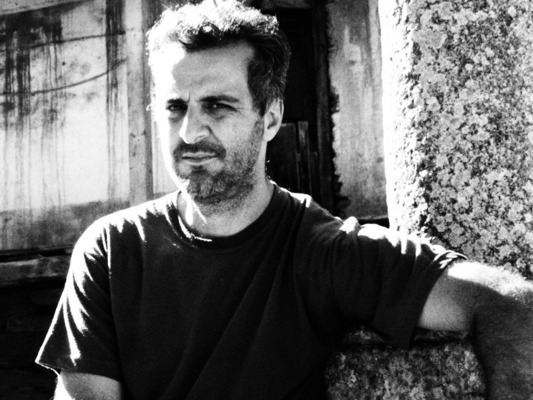

I was reminded of this resilience and imagination recently when watching the documentaries of the Iranian filmmaker Mehrdad Oskouei. Oskouei has focused his camera on troubled youths in Iran for over a decade. These films – set at a center for drug-addicted boys, as is the case with It’s Always Late for Freedom (2007), or at a home destined for young girls who have committed murder, as in his latest, Sunless Shadows (2019) – are marvels of tenderness, solidarity and closeness. I’m struck how often these films are, in fact, mischaracterized. It’s jarring to see the word, “victim,” in descriptions, when, in fact, if there’s one thing that Oskouei consistently avoids is painting his protagonists as victims. Which isn’t to say that he doesn’t portray suffering. Indeed, the anguish, and sometimes also regret, that Oskouei’s films convey are immense, as is a sense of injustice which some of the boys and girls have suffered. But Oskouei is dedicated to their selfhood, first and foremost. It’s Always Late for Freedom revolves around the desire to be free, on one hand, and the knowledge that it means leaving behind your friends on the other. Friendship is a feeling and a state so intense for the boys, its power so primary to most other identifications, sometimes even with parents or siblings, that itself becomes a balm, if not always salvation.

Friendship is a powerful theme in Sunless Shadows, the latest film in the cycle. Oskouei films girls who have murdered abusive patriarchal figures – most often, their fathers – sometimes with the help of their mothers. Given the theme, one may not expect to enter a facility brimming with life. And yet, the girls find ways to support and to celebrate each other. In one striking sequence, Somayeh, a friend visits from outside, confessing to the girls that “normal life” pales to the camaraderie she felt inside the home. In a beautiful shot, as the girl leaves her friends behind, she turns to the camera and restates that the home, with the other girls, is where she feels most “at ease.” It’s a striking, bold statement that rephrases a punitive facility as shelter, a home, a network. We see this again and again, in the girls’ playing charades, in studying together for exams, in caring for one of the girls’ baby, which, we can only guess, will eventually leave the place, with or without his mother.

Cinema’s artifice is a unique tool for the kind of closeness that Oskouei seeks. In the film’s first shot a girl, Sara, speaking directly to the camera, addresses a father she has murdered. This eerie, emotionally crushing ghost chamber, is utterly mesmerizing. Hamlet’s ghost couldn’t have more power, as the girls speak to the dead, often with the tenderness and care reserved for the living. To hear their words of accusation, of pain – words they often couldn’t utter while suffering abuse – and then to see them strive to forgive is an astounding cinematic moment. I was reminded of the hypnotism of the human face that Jean Renoir praised in silent cinema. In Oskouei’s echo chamber, the camera stills, it focuses, it gives its rapturous attention. But then there’s an extension: A screen mounted on a wall shows the girl speaking directly to camera to her mother or sister who sits with her back to us. This moment of identification, first the rapture, the hypnosis, then the brusque awakening and the pain of being on the side of the mothers, is purest theater of emotion.

Bound Unbound: Four by Mehrdad Oskouei program streams August 5 – 30 in the Museum of Moving Image (MoMI) Virtual Cinema.