I have such an intense admiration for Vera Chytilová’s work that it’s almost impossible for me to see her belonging exclusively to cinema history. Her experimental surrealist film, Daisies (1966), made during the brief period of political “thawing” in the Czech Republic, after 1962, and before the invasion by the Soviet Bloc forces, in 1968, could be a textbook study of combining performance art, experimental animation, and fiction filmmaking. It’s no wonder then that J. Hoberman, when writing on Chytilová for Artforum, linked Chytilová’s legacy to that of Yayomi Kusama. While rewatching the two young female protagonists (both named Mary) in Daisies crash music halls, gorge on giant plates of pastries and act like wrecking-balls everywhere they go, I was reminded of the performance artist Pipilotti Rist’s Ever Is Over All (1997), in which a young woman struts down a street with what resembles a bat, gracefully, fluidly crashing the windshields and side windows of all parked cars (yes, it’s the same video whose motif resurfaced in a Beyoncé video clip). Rist has said in interviews that she wanted to have an artwork in which a destructive impulse felt celebratory and joyous, her response to a feeling of powerlessness when faced with dismissive behavior and comments directed at artists (one could easily though not necessarily add, women artists).

Not surprisingly, this spirit of destruction turned into a joyous fete is what animates Daisies. While the two Maries puzzled some of Chytilová’s critics in the late 1960s, it’s hard not to feel that there is something not only kinetic and cathartic about the energies released in the film, but also quintessentially ’60s: a certain post Warholian sense of consumption reaching its apex, of color, surface, packaging, commercial bliss quickly outliving itself, with nowhere else to go. This might be a hindsight reading, pinning up a bit of our posterior experiences on the film. But Chytilová always straddled both worlds: Neither outright consumerist, but certainly informed by the bitterness of the socialist experience, which was so keenly felt by her contemporaries Miloš Forman and Milan Kundera, to name but two key Prague figures forced to emigrate.

While Daisies is so notorious that it’s tempting to jump right into it, I would recommend diving into Chytilová’s filmography chronologically. Chytilová got into FAMU, the renowned Film School in Prague, after working briefly as a model and then as a clapper at Barrandov Studios. She was 28 when she was finally admitted, supposedly after telling her examination panel that she wanted go to film school because “film was so boring.” She meant the stodgy kind, of course. There’s some sense that Chytilová consumed a good deal of western cinema, American underground movies in particular (hence her appreciation of Cassavetes).

Chytilová’s graduation film, Ceiling (1961) centers on a young woman, Marta, who works as a model, and can’t find herself in the superficial reality of Prague’s swanky nocturnal scene. Part of this dissolution has to do with being maneuvered by older men, without her own sense of direction, after giving up her university studies. Ceiling is a great place to start, if anything else, to see how Chytilová negotiated the common push to present the city in opposition to a more wholesome village life (here glimpsed when Marta finally gets fed up with her city travails, and hops on the train, where another older woman offers her a piece of homemade cake; the entire scene framed as a return to the simpler, more authentic life, symbolically linked to the open fields passing by the train’s windows, and to the mother’s modest appearance).

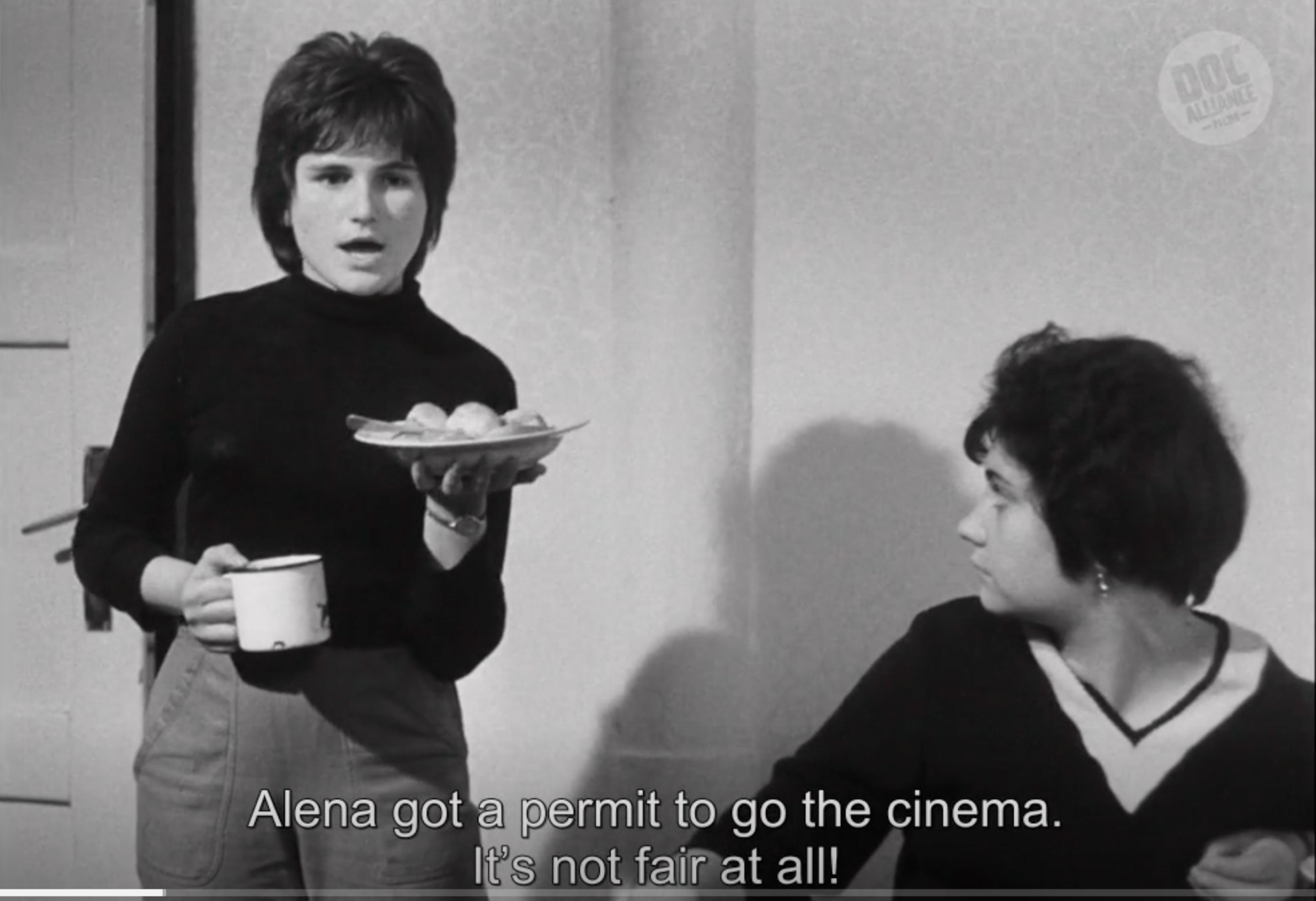

Chytilová looks again at young women’s lives in her debut film, A Bagful of Fleas (1962), a wonderful semi cinema vérité romp, in which the young woman Eva (whom we see onscreen but for a glimpse, at the very end) is filming her rebellious friend, who lives in communal factory housing. One wouldn’t need to search far for ample stories from Eastern European cinema about young workers flooding to cities, and having to negotiate their “country bumpkin” mentality with bewildering cosmopolitism. To some extent, Miloš Forman’s Loves of a Blonde (1965) adheres to this scenario, as does Marta Mészáros’s Don’t Cry, Pretty Girls! (1970). In Poland, Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Camera Buff (1979) is perhaps closest to Chytilová’s approach, since both filmmakers turn the camera into a plot element, and the filmmaker into a protagonist.

Still, Chytilová is a precursor to the films I mention, and one can’t help but be energized by her innovation in narrative voice, which stems from the technological apparatus: In Bagful of Fleas, the embodied camera has a voice, in the sense that we hear, from time to time, the filmmaker (aka “Eva”) whispering from behind the camera, sometimes commenting on what’s happening, other times addressing her friend directly, still others, suddenly breaking into a tune, vastly expanding the sense of diegetic sound (not only music that the girls are listening to on the radio, but also now the voice that joins it from behind the camera). This voice, nevertheless, is pointedly far from the stodgy voiceovers of yore. Where in documentary filmmaking, such voice was meant to shape and to instruct the audience, the voice devised by Chytilová hardly illuminates the tale. Instead, it’s emotive; it brings us directly inside the action, as co-conspirators of these young women.

After A Bagful of Fleas, it is probably time to jump into Daisies and the equally audacious Fruit of Paradise (I wrote more about them for Hyperallergic, when Chytilová’s films played in a retrospective at DocLisboa). But I also encourage viewers to then continue with Chytilová’s Story from a housing estate (also know as Prefab Story, 1979), which, in a way, resumes her cinéma vérité meets black comedy style of previous years. The film, which revolves around a series of loose vignettes on a communist mega-bloc estate, was made already when Chytilová was facing enormous professional difficulties, after the communist crackdown on civic freedoms and art, in 1968. Chytilová’s older films, including Daisies, were censored, and some of her more recent projects were being taken away from her, with funding a constant worry. Chytilová resorted to doing commercial work for television (apparently under the name of her husband, the cinematographer Jaroslav Kucera, who had collaborated with her on both Daisies and Fruit of Paradise).

And yet, as I’ve written in Hyperallergic, with Prefab Story, Chytilová seems to have dribbled the censors in showing yet again, and perhaps with even greater acuity, the dismantling of a utopian socialist dream. She got her last word.