This year, the international film festival Olhar de Cinema, based in Curitiba, Brazil, presents a number of fascinating archive-based films. Among them, there is Fakir, by Helena Ignez, The Pink Indian Against the Invisible Beast: Noel Nutels’ Battle, by Tiago Carvalho, and A Flecha e a Farda (which translates literally to The Arrow and The Uniform), by Miguel Antunes Ramos.

Perhaps even more than an actress well-known for her roles in the Marginal Cinema films, such as Rogério Sganzerla‘s A Mulher de Todos (1969) and Copacabana, Mon Amour (1970), Ignez is, in many ways, a feminist icon whose versatility and passionate political stance transcends the era in which she initiated her film career. This latter role hasn’t yet been fully explored, in terms of her collaborative input and the extent to which Ignez helped construct the image of Cinema Marginal, vis à vis the directors she worked with (a role that could be construed in the vein of Laura Mulvey’s re-contextualizing of Marilyn Monroe’s later roles).

Ignez herself performs this kind of re-contextualization in Fakir, casting her gaze on female entertainers. She looks back on rich archival materials from the 1920s to ’50s — primarily photography and newspaper clippings — to follow the stories of a number of women illusionists, snake charmers and hunger-artists. For some three decades, at the peak of the public’s interest, these artists are veritable pop stars, with careers made virtually overnight. Young, beautiful women, particularly. Under the original teachings and instruction from male fakirs, these women are voluntarily locked in glass enclosures, beyond reach and yet under the fans’ unwavering gaze, while they sleep on knives, brave (or are occasionally bitten by) snakes, persist without food for record-setting periods, and at times, suffer inevitable breakdowns.

Ignez brings back the era when fakirs were not only revered media sensations in Brazil but also belonged to a larger international entertainment and sports circuit, with competitions in Europe and stars’ fame stretching to Hollywood.

Ignez has a keen eye for the real stories behind media sensationalism: a young female fakir murdered by her jealous husband and business partner, another with a small child (presumably out of wedlock), whom she pretends is just a “fan,” like many others, so the girl can follow her mother to events. Under the watchful eye of the crowds, the women trade in their sensuality, attracting larger crowds than men, while hiding realties of their backgrounds and lives — clearly in a double position, where the public opinion makes some allowances for their exceptionality, but never entirely beyond opprobrium (which Ignez makes clear stressing stories of those women fakirs getting arrested and jailed for prostitution, not to mention beaten by the police and in confinement). Ignez eventually brings us to the present time, to what illusionism and fascination with snake-charmers looks like today, though admittedly, it’s a tame ghost of the time when it drew tremendous crowds.

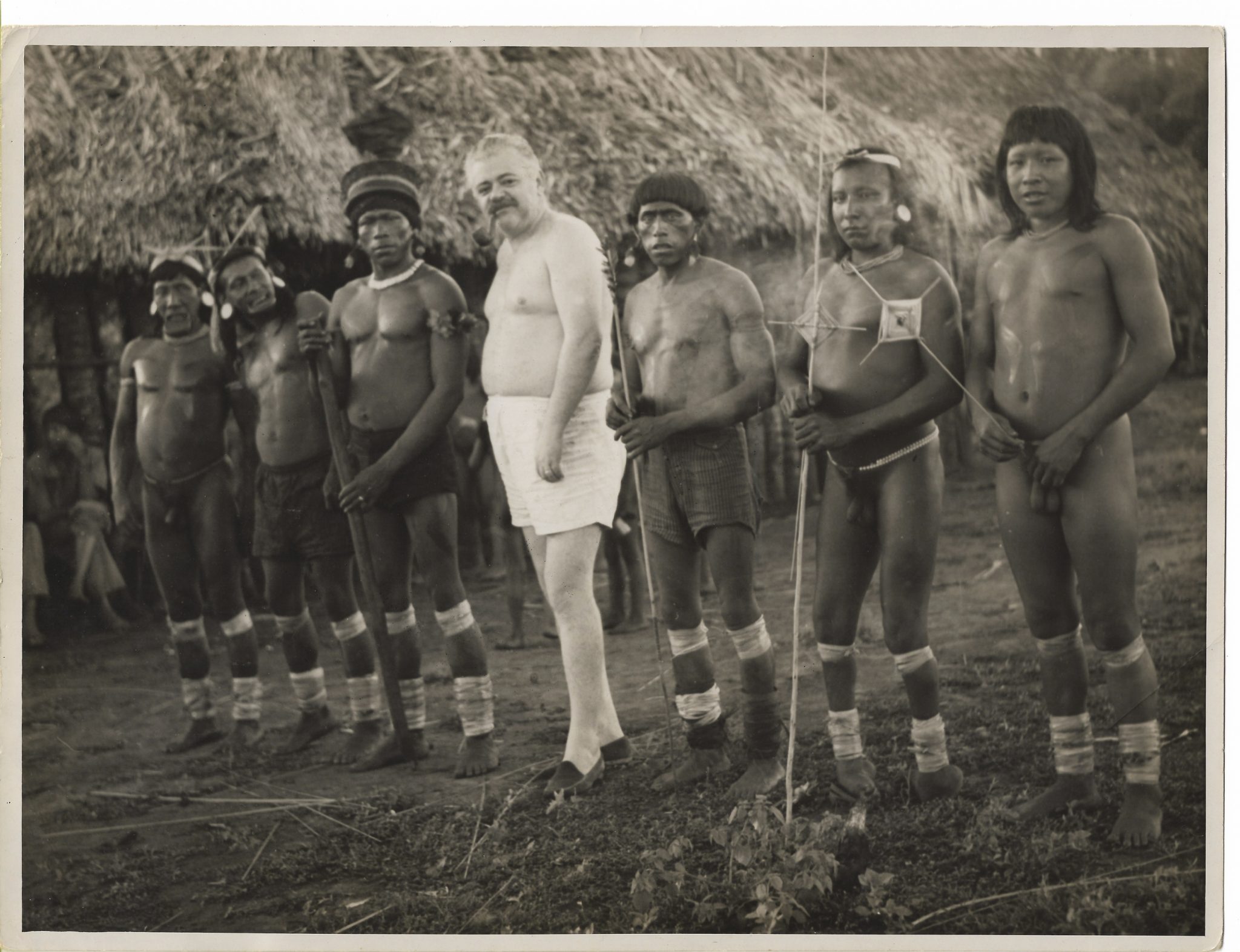

Two particularly rich archive-based films at Olhar are a reminder that Brazil’s history is vast and complex enough to continuously yield under-explored threads. Tiago Carvalho’s The Pink Indian Against the Invisible Beast: Noel Nutels’ Battle centers on the story of a Ukrainian-born doctor, Noel Nutels, who spent decades working in the Amazon region, treating Indigenous communities. Nutels’ story has been disseminated before, albeit primarily in fictional form (at least two novels were based on his life), but it’s only now, thanks to Carvalho’s deliberate combing through the extensive archival materials — based on Nutels’ own 16mm footage — that we have some visual sense of the doctor’s travails. The doctor’s voice is also recoded, in a clip from 1968, when Nutels testified about the Indigenous question before a parliamentary commission, CPI. What is there is incredibly damning, as expected: Nutels, who dedicates himself to saving lives, is not blind to the reality that, as much as vaccinations are a necessary remedy, they are also a result of the pact with the devil. Each area he visits is either already explored or makes an opening for further intrusion of white Brazilians into the Indigenous territory. That further intrusion results in more Indigenous-owned forest being burned and cleared for pastures and cattle ranches, thus spreading areas of deprivation, where the Indigenous communities starve.

Carvalho’s ample use of Nutels’ recorded testimony provides an essential framework — we’re reminded that the images themselves, as poignant as they are, may not have alone made as forceful an impact. In this sense, Susan Sontag’s passionate argument for contextualizing images with words comes to mind. While the images reinforce Nutels’ assertions about the richness of the Indigenous nations’ lives, as well as his missionary zest and his enormous empathy, it is the words, in the end, that sharply stress that Nutels’ victories are in a larger battle that he deems lost. Nutels doesn’t use the word “genocide,” but his testimony can’t be summed up by any other name.

Somewhat more curtailed is Miguel Antunes Ramos’ archive and observation based documentary, A Flecha e A Farda, though the history it examines is equally, if not more, complex. Antunes Ramos uses extraordinary material that’s mostly recovered from an Indigenous archive (at the Museu do Índio, in Rio de Janeiro). It details the Brazilian government’s creation, in 1970, of a rural Indigenous militia, GRIN. In addition to archival clips, former GRIN recruits from the Krenak nation contribute their recollections of having been recruited by an army captain, and taken to Belo Horizonte, for training — under what appears to have been a false promise of trading militia service for a vague guarantee given to the Indigenous tribes that the land will continue to be theirs. Back in the villages, however, the recruits were asked to police their tribesmen for alleged trespasses against white cattle ranchers, who themselves were often occupying the land illegally, refusing to leave the territory formally demarcated as Indigenous.

Part of the fascination with Antunes Ramos’ film is that he builds from such scant archive, which also lay buried for decades: Since the government didn’t care to preserve the trail of GRIN’s existence, for obvious reasons, precious little film footage remains. Strangely enough, as the director notes, some of it shows the Indigenous guard demonstrating the torture method “pau-de-arara” in a military parade — the perversity of this recorded moment lies in the fact, as the documentary notes elsewhere, that the Indigenous people thrown into jails, including what is referred to as the “Krenak Reformatory,” were far more likely to have been subjected to this torture method than to have ever applied it. In this sense, the logic of the state is doubly brutalizing. Nevertheless, as the elderly who participated in GRIN note, their return to the villages often caused tensions, particularly when the State’s sense of law and order challenged and undermined traditional tribal allegiances. If there is any lacuna in the film’s argument, it’s how exactly GRIN was formed, and the dissolved.