Watching Odoriko, the splendid immersive documentary by the Japanese director Yoichiro Okutani, I kept asking myself what was being left out of the picture. Okutani’s compassionate camera observes the women who work at a Japanese striptease theater, performing at times elaborate, other times more sportive and pointedly erotic dances. Okutani stays so close to his protagonists that the sensation is that of eavesdropping. To this end, though there are glimpses of individual acts, and even stories how one woman picked up the elements of her dance skit from another, most of the action plays out inside the cramped spaces and backstages of various theaters. These are shabby and modest, for sure — none of the sordid or scintillating glamour for Okutani or these women — but also often mesmerizing. We are so locked into the women’s point of view that these spaces end up feeling more domestic rather than mere places of work. In this way, Okutani subtly shifts the sense of agency and power from whoever owns the establishments to the women themselves, as employees and performers.

Okutani places emphasis on the moments when the women are chatting amongst themselves, getting ready for skits or settling together to meals. The men’s presence intrudes at times, for sure, but mostly in brief mentions. There are the regulars who follow specific dancers for years. There are the fans who bring them meals and treats. There are the harmless “grandpas,” but also mentions of the “creeps,” and occasional hints that the dancers’ popularity, in general, and their trade are waning (presumably due to the Internet). But Okutani lets these hints drop without dwelling too long on them, though occasionally the women also mention that the business, in general, can be sordid. We are left wondering at these less sanguine elements, while the male voice on the microphone drones on during picture-taking sessions (women in costumes with the theaters’ clients, a session paid per photo) reminding clients that no touching or photographing of private parts is allowed.

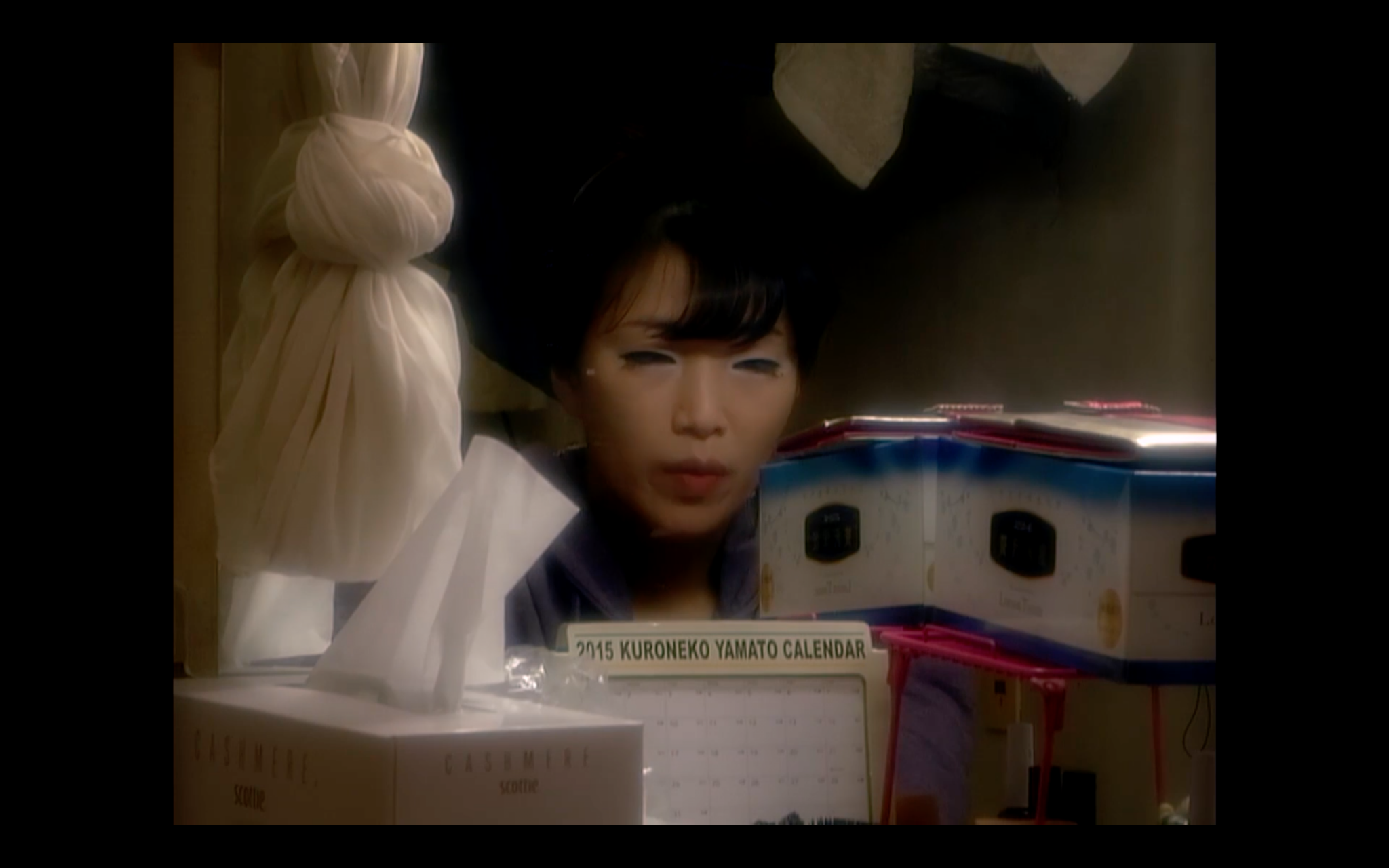

If the social context is opaque, Okutani makes up for the omissions by focusing intently on the dancers. Their joy at sharing meals, their supportive attitudes towards each other, without the catty fights that Hollywood loves to peddle as part-and-parcel of striptease. Moreover, as in Degas’ bath paintings, we get a sense that the behind-the-stage scenes, with their frequent nudity as women walk in and out of dressing rooms to the showers or change into costumes while the camera keeps rolling — the naked body frontal, plain, without prudery — aren’t really about reveling in the nudity, but rather in naturalizing our gaze. The nakedness isn’t alluring as it might be on stage, where seduction is part of an act, but instead is joyful, convivial, soothing when the dancers go about their business not minding the camera or the implied viewers. Other times some tension breaks in, particularly when we come to realize that the dancers are doing their acts back to back, and what the camera catches then are the mere beats of quickly stolen moments, or changes of costume and makeup, between the intense stage work.

While the theater owners are anonymous — and this can occasionally make one wonder if we understand the power dynamics at play fully — what Okutani offers is equally important: The women’s sense of participating in and crafting elements of their jobs. Their collectivity. Their camaraderie. The latter comes through forcefully when a former dancer stops by with her child to watch and support the others. The scene with the child cooing over a pink balloon, the women cooing around it, is so pointedly homely, we can’t forget that some of these women have also raised their families with the money they earn from dancing. Okutani doesn’t stake out any claims, but, in fact, his compassionate vision of these women’s daily routines and solidarity makes a case that sex business ought to be legalized (where it’s not) and formed as women’s cooperatives. The clients are left in the dark, their needs for a minute left to themselves. Odoriko is, if but for glimpse, a women’s world. We may wonder if it’s an idealization but Okutani’s warmly washed and softly lensed aesthetic and the camera so attentive to the women’s bodies, without much voyeuristic drive, makes this postulate of collectivity plausible.

Odoriko made its world premiere in the International Competition at IDFA. For more coverage from the festival, also see the essay from last year.